The Purpose of Purpose: Purpose, Positioning and the Benefit Ladder

So, I’ve talked about…

The difference between purpose as discoverable fact and purpose as useful tool.

The idea of being strategish, which involves both sounding clever AND saying nothing of substance.

And finally, the related do-gooding trend of purpose marketing.

My brain has started to melt a bit with the research I’ve been doing for these articles. And by “research”, I mean googling “brand purpose” and related terms over and over, looking through varying frameworks and definitions.

The most common definition of “brand purpose” is identical with “company purpose” – that is, the non-financial reason for the company existing, the highest-tier objective which makes sense of all other objectives. I’ve already noted several times an apparent inconsistency there: if the brand purpose is a descriptive fact about the company, it’s pointless to prescribing what it should be, and yet agencies and marketers are always coming up with new ones.

But there are some other definitions of “brand purpose” out there. Some are explicit, like Special Group’s:

What is the role we want to play in people’s lives?

Others are more implicit – when you read through their explanations and frameworks, it becomes clear that, for them, brand purpose is an intersection of company and customer.

That one is from Beloved Brands, and oh my God they’re yet another place offering a “Mini MBA”. Ritson should have trademarked the term.

“Builds a beloved branded business” is a bit fucking circular as a criterion in the Venn diagram, but you get the idea – customers need it, you love doing it, there’s your “brand purpose” intersection.

Whether it’s implied as in the Beloved Brands model or explicit as in Special Group’s strategy playbook, this kind of “brand purpose” definition is clearly prescriptive and clearly distinct from “company purpose” as defined above. For example, if customer needs change, then what your brand purpose should be will also change.

And also, of course, in line with common trends in brand-strategy documents, the articulation of this intersection will need to be poetic, inspirational and lofty.

I’ve noted previously the similarities between classical positioning strategy and trying to find the “right” cause for do-gooding purpose marketing. With this “what is our role in people’s lives?” definition of brand strategy, we get even closer to classical positioning and also to a related tool, the Benefit Ladder.

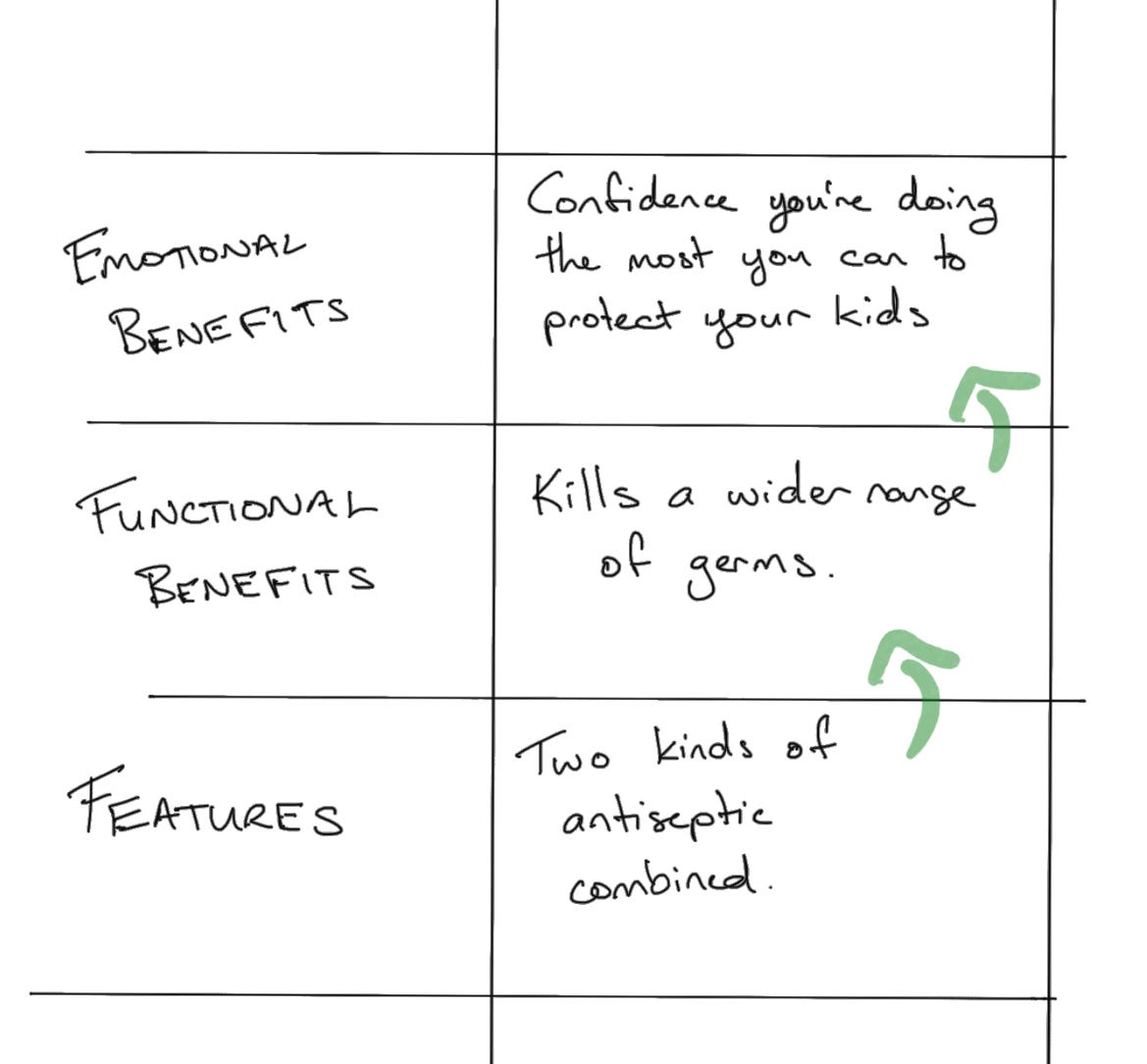

Benefit ladders are super simple and super useful for thinking about possible value propositions for a product, service or even brand. Basically, you start with the facts of the product/service (features), and ask yourself – what useful outcomes do these features enable? But you don’t stop there. You then take those useful outcomes and try elevating further – what desirable emotional outcomes do these useful outcomes enable?

There are three dimensions in a benefit ladder – what the company offers, what the customers want/need, and then the varying depths of those wants/needs. The idea is that if you can understand what emotional motivations underlie the appeal of the functional benefits, you can make that promise more explicit in your messaging and that will appeal more than just promising the functional outcomes and letting the customer determine why they’d want that.

Getting to and focusing on an emotional benefit is not universally useful. There are plenty of categories in which functional benefits are basically where customer motivations sit. In those cases, it’s weird and unnecessary to try to elevate a very simple need into some lofty emotional outcome.

And that’s another situation where someone mechanically following a framework like a benefit ladder can get tripped up. “It says emotional benefits, so I have to come up with emotional benefits or I’m not doing this windscreen-repair brand properly.” The result is writing vague or unsupported emotional benefits into a framework in the hopes that it’s good. At best, it’s pointless. At worst, it diverts attention from the actual effective marketing challenges at the level of functional benefits.

But Ritson gives good advice: go as far up the benefit ladder as you can. Just no further.

Related to benefit ladders are positioning statements, which are typically tools for competitive strategy. Like benefit ladders and value propositions, they intersect the dimensions of customer need/want and company offering. But they go a step further and consider the competitive environment too.

They are tight and prosaic answers to the question: “How does what we do create value for customers in a way that’s better than competitors for some reason?”

And in line with the elevation on a benefit ladder, these positioning statements are often more powerful if they focus on promising a differentiated emotional outcome than merely a functional one.

I bring these tools up because several of these alternative definitions of “brand purpose” seem to be basically repackaging benefit ladders and positioning statements. Perhaps with slightly loftier language.

Let’s take Special Group’s “what is the role we want to play in people’s lives?” It’s a great question for any business, not just from a branding perspective. One some level, “the role we play” is another way of saying “how we create value”, and understanding how you create value for customers is at the heart of successful business.

Presumably Special wouldn’t be satisfied with a prosaic answer to that question. That is, if we ask what the role of the Masterfoods herbs & spices brand plays in people’s lives, Special aren’t looking for: “Supplying all the herbs and spices you need for home cooking.” Even though that’s technically accurate.

What’s missing from that explanation of Masterfoods’ role? Well, obviously, there’s no emotion in that statement, and there’s plenty of emotion in home cooking. Home cooking often means cooking for others – you want it to taste good for them, you want it to be healthy for them. Then there’s self-image, how you want to see yourself as a home cook (home chef!)

Another thing that’s missing from that explanation of Masterfoods’ role is a competitive element. Who are Masterfoods’ competition? In New Zealand, there are supermarket store brands like Pam’s and Select. There’s Mrs Rogers, with its compostable packaging. There are some specialist meat-spice brands. And so on.

Let’s say that some research shows:

Mrs Rogers is the largest competitor.

Customers find the compostable Mrs Rogers boxes appealing for environmental reasons.

Customers find the compostable Mrs Rogers boxes a bit of a messy hassle in practice.

Many customers strongly wish their kitchens and pantries were more organised.

The core products of Masterfoods and Mrs Rogers are indistinguishable commodities – outside of minimal health standards, ground cumin is ground cumin. The differences in the products are in the packaging. Mrs Rogers with compostable eco-packs and Masterfoods in uniformly sized plastic containers with bright colours:

Now, if I’m Masterfoods taking on Mrs Rogers, I’d do a few things:

Build some minor messaging and visibility of the recyclable plastic packaging to partially neutralise Mrs Rogers’ advantage for eco-conscious customers.

Keep maintaining the quality and perception of quality of the products – this is table stakes for the category. Pun intended?

Lean into what the beautiful uniform packaging enables, which Mrs Rogers cannot.

Our research found that a large number of customers wish their kitchens and pantries were more organised. A bit more digging and conversations with customers reveals that this is related to a few different things – aspiring to a self-image of a super-organised home cook, wanting to live in a nicer space, being conscious of how these spaces appear to visitors, etc.

So what’s the emotional benefit which Masterfoods can offer and its main competition would struggle with? It’s the feeling of being an organised home cook (chef!), or the feeling of beautiful cooking spaces, etc. “Beautiful food comes from beautiful spaces” or some shit like that.

Now go back to Special Group’s definition of “brand purpose”. What should be the purpose of Masterfoods in customers’ lives? Perhaps it’s “the secret to our customers’ success in the kitchen” or “turning home cooks into home chefs” or “bringing beauty to everyday cooking”. Any one of those (perhaps especially the last one) depositions the competition, leverages the strengths of the products/packaging, and speaks to aspirational emotional desires of customers – all in a commoditised category the core products are identical to each other.

So in this case, in contrast to those definitions of “purpose” which are “the reason the company exists”, we have a strategic choice, a prescription for commercial success, which is dependent on facts about the company, the customers and the competition.

With a well-developed positioning statement and benefit ladder, is there any real need for this definition of “brand purpose” to be included and filled out?

Well, maybe. Positioning statements are useful, but long. Punchy versions of them which distill the various elements of positioning into a single thought are powerful and useful. A little bit of poetry is fine for making it punchy and inspirational, but the usefulness comes from the simplicity, not the loftiness – mistaking one for the other leads to lofty and vague statements when simple and prosaic would do the job much better.

As always, clarity of thought and understanding behind the purpose of these different fancy-labelled framework elements is more important than following some formula.