The Purpose of Purpose: Company Purpose vs Brand Purpose

Is purpose supposed to stay the same? Or is it something that keeps changing? Or is it both?

In business and marketing, the term “purpose” is used in various ways, by various people, with varying levels of vagueness. It’s a mess, so I want to keep prodding it from different angles. Prodding it reveals which parts collapse because there was nothing much to them, hopefully leaving behind something substantial.

We can define company purpose as that organisational objective which rationalises all other objectives. In commercial businesses, that is either maximising shareholder value or whatever sits higher in the hierarchy than maximising shareholder value – if anything.

The idea of a company purpose is not new. 15 years before Simon Sinek TED-talked a load of nonsense that everyone lapped up, the Harvard Business Review published a 1996 article entitled “Building Your Company’s Vision”. It was written by Jerry Porras and Jim Collins (five years before he published Good to Great). They laid out a framework which included:

Core purpose

Core values

Big Hairy Audacious Goal

Vivid description

(Yes, this article is the origin of the popularisation of “BHAGs”.)

They defined “core purpose” similarly to how I have defined “company purpose” above. As with my previous post about Mindy from Animaniacs, Porras and Collins recommended asking “why” over and over to reach this core purpose. And they were perhaps a little less cynical than I about how often that final answer is “money”.

To dramatise the difference between shareholder value and a non-financial core purpose, Porras and Collins suggested this fun little thought experiment:

The Random Corporate Serial Killer Game

Suppose you could sell the company to someone who would pay a price that everyone inside and outside the company agrees is more than fair (even with a very generous set of assumptions about the expected future cash flows of the company). Suppose further that this buyer would guarantee stable employment for all employees at the same pay scale after the purchase but with no guarantee that those jobs would be in the same industry.

Finally, suppose the buyer plans to kill the company after the purchase—its products or services would be discontinued, its operations would be shut down, its brand names would be shelved forever, and so on. The company would utterly and completely cease to exist.

Would you accept the offer? Why or why not? What would be lost if the company ceased to exist? Why is it important that the company continue to exist? We’ve found this exercise to be very powerful for helping hard-nosed, financially focused executives reflect on their organization’s deeper reasons for being.

Porras and Collins also note that a company’s core purpose should last for “at least 100 years”, in contrast with “specific goals and business strategies”, which should change many times in 100 years.

Whereas you might achieve a goal or complete a strategy, you cannot fulfil a purpose; it is like a guiding star on the horizon – forever pursued but never reached. Yet although purpose itself does not change, it does inspire change. The very fact that purpose can never be fully realised means that an organisation can never stop stimulating change and progress.

(Me being cynical again – this does also describe maximising shareholder value.)

It’s instructive that every explanation of the impact of the core purpose refers back to the motivation of the employees of the company:

When a Boeing engineer talks about launching an exciting and revolutionary new aircraft, she does not say, “I put my heart and soul into this project because it would add 37 cents to our earnings per share.”

Which is not to say that the customer is absent from the equation – it is what the company does for customers that is presented as the deeper motivation for the employees. But the emphasis is on motivation, comprehension and unity among the company’s team members.

Now, contrast the above with the way “brand purpose” is commonly used.

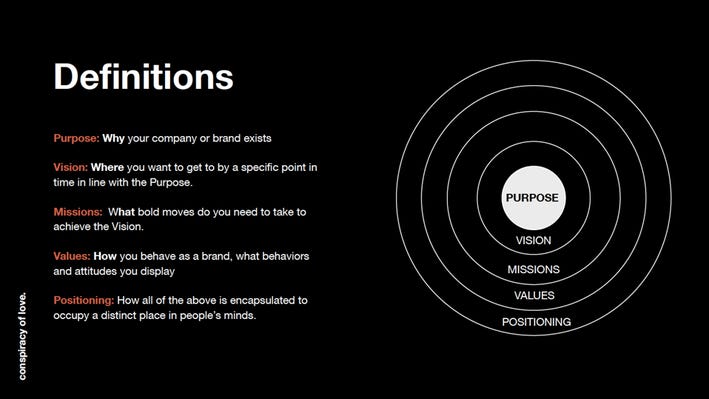

Firstly, brand purpose is typically part of a brand strategy, including its place in a brand strategy on a page kind of framework. These frameworks tend to include elements like:

Purpose

Vision

Mission

Values

Brand proposition

Reasons to believe

Tone of voice

I won’t explore all of these elements here. I’ll just note that some of the elements are similarly vaguely or inconsistently defined depending on who is using them. For example, a quick Google finds one LinkedIn post confidently asserting that “mission” is “why we exist”, while a framework from Forbes defines “mission” as “what you’re going to do today to achieve your vision”.

Ignoring ostensible definitions for a moment, how do we see brand strategies being used (and all the components that come with whatever framework is involved)?

Well, for a start, they often seem to change at least as frequently as a client’s brand agency does. Depending on the scope of agency engagement, agencies will often include a proposed brand strategy as part of a competitive pitch to win the business. And if they’re using a branding framework that includes “purpose”, they’ll include a proposed purpose in their pitch. That can mean a client is receiving five or six proposed “brand purposes” to choose from in the process.

Even if a brand strategy is not part of the pitching process, the appointed agency will often kick a new relationship off with something like a “brand strategy audit” or just jump straight to “doing a brand strategy” for the new client – to lay down a foundation for subsequent brand work. And if they’re using a framework that includes “purpose”, one will be generated.1

Finally, forgetting agencies for a moment, newly appointed CMOs will often want to make their mark in a new role with a new brand strategy that includes – you guessed it – a new brand purpose.

At this point, there are two logical possibilities.

The “purpose” element of these brand-strategy frameworks is supposed to refer to the unchanging company purpose and everyone is fucking it up by proposing new ones every few years.

The “purpose” element of these brand-strategy frameworks is different from company purpose, as evidenced by everyone’s willingness to change it every few years.

Keen-eyed readers will note that this, again, is the difference between purpose being descriptive and prescriptive. A descriptive purpose is a fact about the business, whether or not it’s yet been articulated. A prescriptive purpose is a strategic choice, made with reference to some higher-order objective.

If “brand purpose” is just another term for “company purpose”, which we’ve already identified as being descriptive, unchanging for 100 years, and so on, then no agency strategists or new CMOs should be proposing new purposes in their brand strategies. They should receive the existing purpose, slot it into that section of their brand-strategy framework, as the previous agency/CMO should have and as future agencies/CMOs should do, and change the other elements depending on circumstances.

But if “brand purpose” is a strategic choice and not simply the objective of strategy, then “brand purpose” is different from “company purpose”. In which case, there’s no inherent problem with it changing as circumstances evolve, and in fact there’s no inherent problem with more than one brand purpose being right. Remember, if purpose is descriptive, you can only be factually accurate or inaccurate about it. If purpose is prescriptive, then purposes can be better or worse at being effective.

But if brand purpose is different from company purpose, then what is it? How should we define it?

I think exploring that question will have to wait for next time, or else we’ll blow out the reading time for this article. But here are a few thoughts.

While the question of company purpose is “what is it?”, the question of brand purpose is “what should it be?”

If the question is “what should it be?”, what factors would inform the decision?

Just because the definitions and roles of “company purpose” and “brand purpose” are distinct, doesn’t mean that they can’t be the same – that is, depending on how we define brand purpose, a company purpose might make a very good brand purpose.

And I’ll leave you with Special Group’s definition of brand purpose as food for thought:

Is that different from “why we exist”? Could the answers be the same? Could the answers be different? How could Special’s definition be a way of approaching the question “what should our purpose be?”?

I should note that, while this is common, it is not universal. Certainly I would have been laughed out of the room if I had proposed changing the brand purpose of global clients like Netflix or Red Bull. (I actually did once foolishly propose changing the brand purpose of Microsoft and was, unsurprisingly, laughed out of the room.)