The Purpose of Purpose: Strategishness

All truth is poetic but not all poetry is true.

In my last post, I talked about the difference between company purpose and brand purpose. I noted that all definitions of company purpose entail it being generally unchanging, the reason the company exists, a fact about the company to be discovered, rather than a choice to be made.

Which leaves the question of what “brand purpose” might be in contrast – that if it is different from “company purpose”, it can be a strategic choice, and it can be changed many times while the company purpose remains the same.

To explore potential definitions of “brand purpose”, I will look at those definitions out in the world, excluding the ones which just restate “company purpose”. As an example, I provided Special Group’s definition: “The role we want to play in people’s lives.”

When I started looking around at examples, I found it was difficult to explain my thinking without first introducing a particular new concept. So, as an interlude, let me explain this thought.

In 2005, in the first episode of The Colbert Report, Stephen Colbert coined the term “truthiness”, partly as a way to describe George W Bush’s vague hand-waving in justifying the illegal 2003 invasion of Iraq. The term filled a gap in the English language, it became Word of the Year, was added to dictionaries, and was also adjectivalised (which is my verbification of the adjective “adjectival”) into the word “truthy”.

I find there is a similar gap in language when I try to describe a certain phenomenon which pervades brand strategy, marketing strategy, and perhaps strategy in general. And that is the jazz-handy poetic impressive-sounding-yet-somehow-devoid-of-any-practical-meaning nonsense that is so often passed off as “strategy”.

For lack of a better word, I have often found myself describing things I’ve read (and occasionally written) as “strategish” rather than “strategic”. (Pronounced strah-TEE-jish.)

It’s particularly prevalent in brand strategy for a few reasons.

Brand is (correctly) seen as something that exists in people’s heads, something conceptual, which seems to open the door to vagueness.

Some elements of brand are emotive rather than rational, and because emotions are best conveyed with poetic rather than prosaic language, it may seem as if brand strategy is therefore best articulated in poetic language.

Most marketing strategists have no formal education in brand strategy, which doesn’t bother any of them, because of the above – it seems crazy to think about formal education in brand when brand seems so creative, poetic and emotive. I’m not saying that formal education is necessary for doing brand strategy, just highlighting a certain lack of agreed standards. (In fairness, even among formal educators.)

There is low accountability in brand strategy, because its impacts are long-term, gradual, and difficult to distinguish from confounding environmental factors.

Finally, add to this mix the context of brand-strategy work. The people who are doing brand strategy are either agency strategists or marketing leaders. In either case, they have two audiences to think about: the market and whomever they’re presenting their brand strategy to. For agency folks, the latter means the client. For marketing leaders, that means exec teams and boards.

By far the dominant success factor of their brand strategy is how it is received by the people they present it to, rather than commercial success in the market.

Without defining what’s involved in each, let’s hypothesise that there are two kinds of brand strategies – strategic and strategish.

A strategic brand strategy results in commercial success in the market.

A strategish brand strategy feels really… strategish… to clients/execs/boards. They’re left thinking either “wow, that feels so right” or sometimes “that’s so clever that I didn’t even quite understand it myself!” But it has no real substance to it.

Now, effectiveness and saleability are not mutually exclusive. A brand strategy can be both effective and also feel right and appeal to clients/execs/boards. In fact, effective brand strategies will indeed tend to ring true, feel right. But brand strategies can “feel right” without being effective. And let’s also assume that it’s easier to make a brand strategy feel right than to feel right and be effective.

So what happens over time? Well, if clients/execs/boards judge brand strategies on “feeling right”, then in an evolutionary sense, strategishness is the more advantageous trait. Strategish brand strategies will win pitches. Strategish brand strategies will be approved by clients, execs and boards. Agencies which produce strategish strategies will profit. The careers of strategists who produce strategish strategies will flourish. Training courses teaching strategishness will fill seats – and those students will profit too.

It’s not that effectiveness is a hindrance – it’s just incidental. Some of the strategies will be effective, most neither good nor bad, a few counterproductive. But by the time that’s discovered, the strategish CMO or agency strategist has moved on to a new role, buoyed by their success in strategish-sounding strategy, and the brand agency has probably been replaced. And even if they haven’t, who’s to say why commercial performance hasn’t improved? There’s Gen Z and climate change and the recession and… AI… the TikToks…

I want to be very clear about something. In this hypothesis, strategish strategists are not (necessarily) con artists. The CMOs and agencies producing these strategish strategies are doing so because they believe that’s how effective brand strategy is done.

And who can blame them? Everyone successfully doing brand strategy around them seems to be doing something similar. Even when looking at effective brand strategies, it may be the “feeling right”-ness of them that stands out and is mistaken for the sufficient cause of their effectiveness. So they try to replicate it.

And we also have fabulously successful thought leaders like Simon Sinek saying strategish things like this with a straight face:

People don’t buy what you do; they buy why you do it.

I mean, it’s just obviously nonsense. People don’t buy why you do it, they buy why they do it. People have a lot going on. You’re just not that important in their lives and you don’t need to be.

But it feels so good to say. It looks so good on a presentation slide. You put that up and the CEO goes, “Oh wow, shiiiiiiiit. People buy whyyyyyyy we do it. Oh man, for sure.” And then the next slide is, “And here’s our why.” And the CEO goes, “Fuuuuuuuuuck yeah. That is totally our why. Goddam, does that…? It rhymes! Shit, it rhymes and three of the words start with the same letter. Oh man, that’s the whyest why I’ve ever seen.”

Okay, end of hypothetical. I digress. And I exaggerate to make a point. And that CEO was clearly high. And there are other related points I would like to make, for example about the inherent value of consistency for consistency’s sake.

My point is that it’s a very believable scenario, that a whole culture of brand strategy could evolve which rewards and replicates a certain jazz-handy vague poetic sophistry with near-zero accountability.

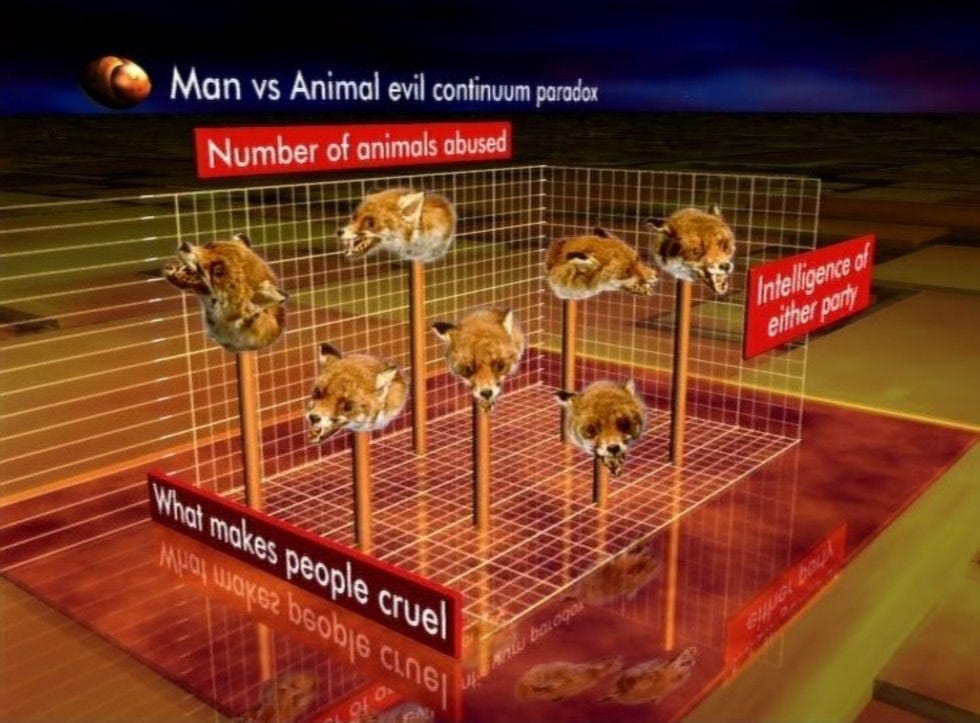

For now, let me at least just table this notion of strategishness, of phrases and diagrams which…

Give a strong feeling of cleverness and meaningfulness

Can be very compelling for internal and external clients

While having remarkably little practical value and/or commercial impact.

Because as we dive into the world of alternatives to “company purpose” as definitions for “brand purpose”, I fear we cannot explain what we find without it.