The Purpose of Purpose: Doing Good

Superman does good. Businesses do well.

I’ve already noted that people can’t seem to agree on what “brand purpose” means. About half the definitions line up with Jim Collins’ and Simon Sinek’s definition of “company purpose”, but that just brings us to the other problem: people also can’t agree on whether or not companies have purposes beyond maximising shareholder value. Don’t worry, you haven’t blinked and missed anything – I still haven’t yet gone through some of those alternative definitions.

(We can all at least agree that non-profits have a non-commercial purpose, by definition.)

Another confusing factor is the related but different idea of “purpose-led marketing”, which seems to include both a particular definition of “brand purpose” and a particular theory about effective marketing.

For what’s called purpose-led marketing, the “brand purpose” can’t just be “our non-financial reason for existing” or “the role we want to play in our customers’ lives” or whichever other definition of brand purpose you use. According to this approach, brand purpose has to be about doing good in the world.

And further, the idea is that if you’re doing a kind of good that aligns with your audience’s values, they’ll favour your products and services.

Here’s an example of this kind of thinking from an article two years ago entitled Why Purpose-led Marketing is the Future of Brand Growth.

Traditionally speaking, the main goal of a retailer is to sell quality products that serve a specific need for their target market. But over the years this goal has changed, and in the current competitive climate, consumers are spoilt for choice when it comes to brands. As such, they’re no longer attracted to traditional differentiators such as price points or product quality. This is not to say competitiveness on price or quality is redundant, they just no longer provide a significant advantage in our current retail landscape – more so since the pandemic. Instead, consumers are more likely to engage, trust and purchase from purpose driven brands that uphold strong values.

…

The whole point of being a purpose led brand is to actually make an impact. Above driving sales, gaining market share or increasing brand awareness it’s the positive impact that your purpose can have on society and your potential to make a change. This not only benefits your business but also speaks to your consumers who are directly affected by that issue.

That pretty succinctly sums up the view we’re talking about.

So, a few thoughts here.

Firstly, as I said above, depending on your definition, this is clearly a narrower subset of brand purposes. If you’ve spent a lot of time around purpose-led marketing, you could be forgiven for thinking that a brand purpose must always be some kind of noble social or environmental cause. But take this stated brand purpose for example:

To be the world’s best at satisfying consumer moments in tobacco and beyond.

That is (or perhaps was) British American Tobacco’s brand purpose, and I don’t think anyone could mistake that for doing good in the world.

Proponents of the more narrowly defined purpose-led marketing would probably say that BAT’s statement is not really a brand purpose, or they might say that purpose-led marketing requires some additional kind of good cause added to the mix. The point here is that purpose-led marketing assumes a social or environmental good as the cause or purpose.

Secondly, let’s take a step back to my earlier distinction between a purpose that’s a discoverable fact about a company (description) and one that’s a strategic choice of how to achieve success (prescription). Which kind is this “making the world a better place” sort of purpose?

In theory, it could be either. If such a thing as non-financial company purpose exists (I have to say that so often that I should make an abbreviation for it)… then a company could be founded to promote some kind of environmental or social good in the world. That is its purpose, the intention of its founders.

An example of this could be a business founded to address some unfairness in the existing market. Some people note that plus-sized women are under-served by the current industry and start a business to address that. On one hand, that’s smart business – meeting the needs/wants of an under-served market segment is classic business strategy. On the other hand, it’s a social cause – inspired by a belief that women shouldn’t have to compromise on fashion depending on their size.

That is a case where the company’s purpose can play the role of the “good cause” brand purpose. And one might say, it’s all very well to shine a light on the noble intentions of businesses founded to address some social or environmental ill, but…

While every successful business is founded to address some under-met need or want, most consumer or business needs/wants don’t fit the usual definitions of good causes. If purpose-led marketing involves some social or environmental cause and your business was founded to provide more effective removal of stubborn stains, what are you supposed to do?

Well, that brings us to the matter of prescriptive purposes for purpose-led marketing. Since you don’t have a noble cause at the heart of your business, you’re supposed to find one. And not just any one – the right one. How is that decision made?

Such a cause is not chosen at random. Every proponent of purpose-led marketing will tell you that your purpose must be authentic, which might seem tricky, since you are now essentially working out which cause will make you the most money. In terms of authenticity, it must have some reasonable connection to what your business does and shouldn’t contradict how your business does it.

Then, if the theory is that customers are more likely to buy a brand aligned with a cause they believe in, the cause should be one that most of your target customers believe in.

Finally – and I haven’t seen this talked about so much – I am assuming that businesses are also told to choose a cause (or a particular approach to a cause) that competitors have not already chosen themselves.

If the above sounds familiar, it could be because you have some experience with positioning. Firstly, what is the intersection between what you can offer and your customers want?

And then how or what do you offer that competitors can’t?

In other words, proponents of purpose-led marketing recommend that your purpose/cause be:

Authentic – it should make sense in light of the commercial activities of your business, the value proposition of its products, etc.

Appealing – it should be close to the heart of a significant number of your target market or market segment.

Differentiated – it should be recognisably distinct from any causes competitors are championing.

Note that there’s another aspect of authenticity which is “not faking it”, ensuring consistency of operations with purpose, etc. Coca-Cola attracted some criticism recently for doing some clever ads about recycling while being one of the bigger polluters out there. (I doubt that’ll stop it being effective.)

Where does that leave our hypothetical stain-removal brand? With some mental gymnastics and some flashy presentation slides, maybe you could make the case that stain removal helps clothing last longer and so cuts down on industry waste in the environment. Like… Hmm. I just came up with that on the fly and it’s not half bad. I should be a jazz-handsy strategisht.

Let’s say that this environmentalism is appealing (my target audience cares about it) and differentiated (no other stain removers are owning this space). The theory of purpose-led marketing is that my target audience are moved by my brand’s tales of environmental waste, support my cause, etc. – and will choose my products over competitors.

With purpose-led marketing, I think we have another of the “post hoc ergo propter hoc” situations mentioned in the last post. That is, commercial results may follow, but not necessarily for the reasons we think.

So, why might identifying a brand with a cause be effective, other than because the audience supports the cause and therefore likes and therefore prefers the brand over competitors?

Well, consider two situations. In one, a brand is differentiated in the traditional sense – it offers something competitors do not. Imagine a brand which offers a range of household cleaning products for pet owners. The brand adopts (hah) rescue-dog welfare as its cause. Pet owners now have a range of brands to choose from in cleaning their house, including this one specially formulated for pet mess and helping find homes for poor dogs just like yours.

Does the customer buy the brand to support saving dogs? Or does the brand’s dog-saving remind the customer about the point of difference of this brand – which suits the customer’s particular needs.

So in that case, the choice of noble cause has reinforced and reminded the customer of the brand’s actual differentiation. As long as other marketing activity is communicating the differentiated benefits of the products. Pretty key point there.

Consider the second situation: a brand is undifferentiated in a commoditised market. That is, its products and competitors’ products are all basically as good as each other for anyone who might use them. Imagine a brand of pet food kibble. The brand adopts (teehee) rescue-dog welfare as its cause. As the customer is walking down the pet-food aisle with 15 different brands, sees one it recognises as the rescue-dog one, picks it up, keeps moving.

Does the customer buy the brand to support saving dogs? Does the customer buy the brand because it feels affinity with the saving-dogs cause? Or does the brand’s dog-saving just make the brand distinctive enough that the customer can make a low-involvement decision of which product to buy among a bunch of brands that will all do the job well enough.

In both cases, we can explain the sales impact of the “purpose-led marketing” in terms of other marketing theories it has supposedly superseded – differentiation and distinctiveness.

A third explanation was proposed to me recently that purpose-led marketing communicates alignment of values, and alignment of values builds trust, and trust is an important component of brand effectiveness.

In all three cases, the purpose-led marketing is one of a number of possible ways to create commercial impact – one way to remind about differentiation, one way to be distinctive, or one way to build trust.

In any case, I do generally reject the notion in the excerpt above that good-doing noble-cause purpose-led marketing is a new essential approach to brand marketing which replaces all previous ones because consumers today are more cynical or caring than consumers yesterday.

There’s another possible reason why noble brand purposes and “making the world a better place” marketing are so popular. And that is that many marketers have felt slightly embarrassed and dirty about their professions.

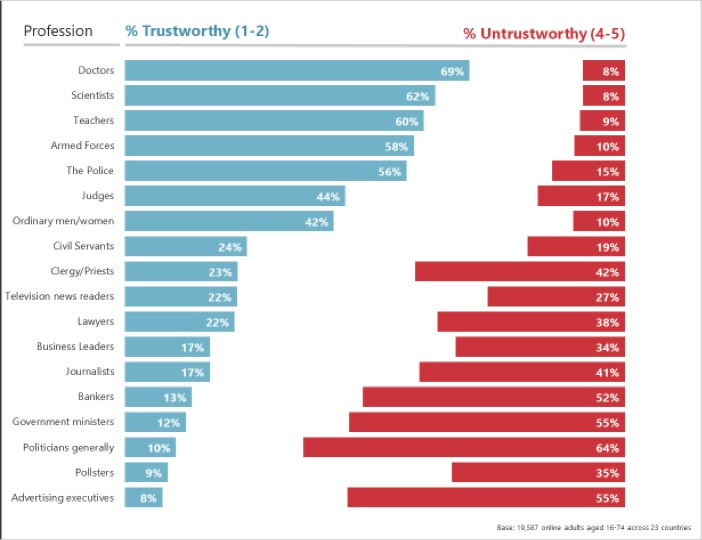

Advertising consistently rates lower politicians and even lower than fucking POLLSTERS for trustworthiness. I mean, dear God. Pollsters.

And who wants that? Plus, so much of advertising is done by creative people, artists and writers, and most artists and writers grow up rejecting the notion of selling out, NO LOGOing their way through university or art school.

So there we are, the least trusted people in society internalising our disdain for being sellouts, and someone comes along and says, “Hey! Did you know that the most effective kind of marketing is SAVING THE WORLD?”

We can be forgiven for not looking too closely at the fine print or noticing how lucrative it is to go around telling marketers that they can be heroes.