The Purpose of Purpose: Company Values and Brand Values

Innovatively disruptive. Creatively courageous. Relentlessly customer-centric. Adverbially adjectival.

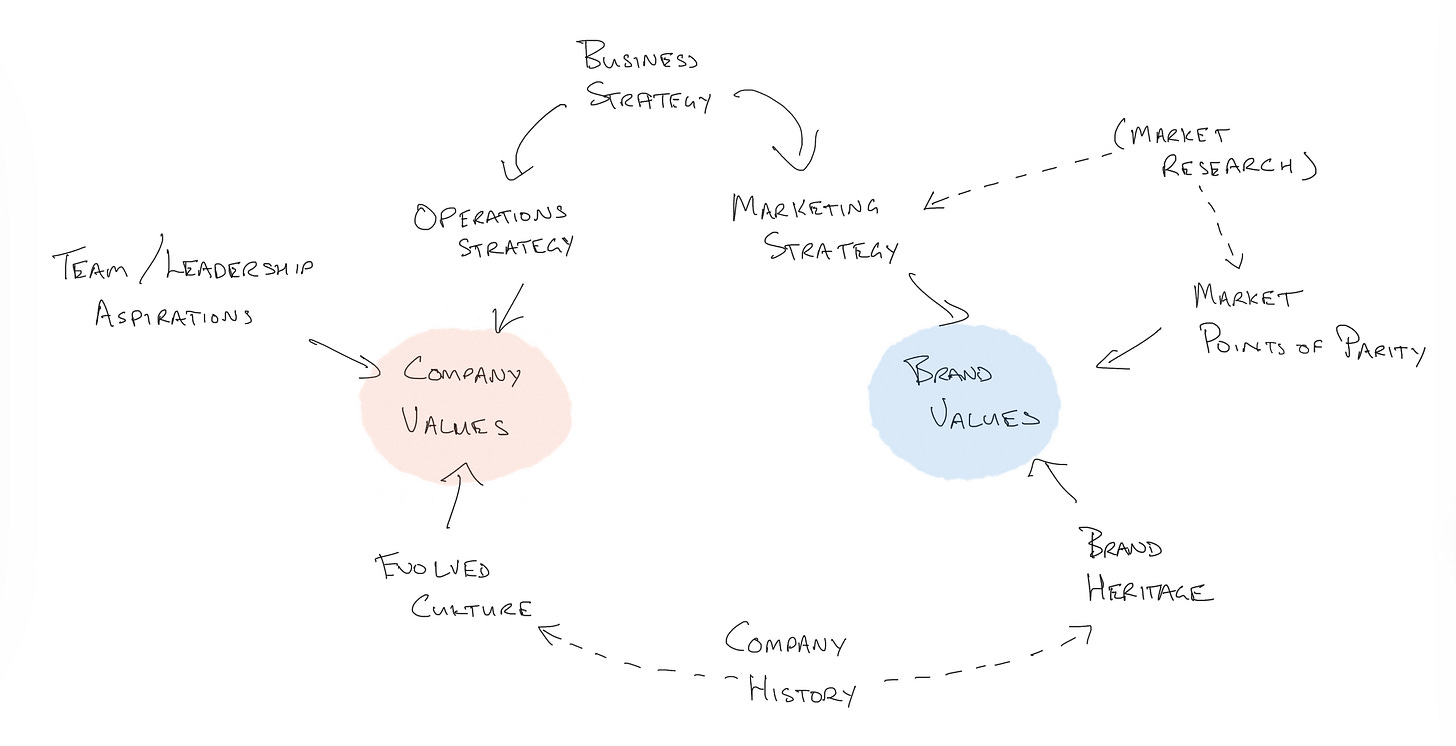

Sitting alongside “purpose” in many brand-strategy frameworks is a section for “values”. Unlike with company and brand purposes, the distinction between company values and brand values is much clearer. But I do still see it causing confusion, especially when people don’t realise there is any distinction at all.

Company values are internal and describe the culture and decision-making guidelines of the company. They’re how we behave, how we do things around here, etc. They might help a prospective employee decide if they’re a good fit for the team. They might help an office manager or HR lead make decisions on social events. They might even help an R&D team pick directions for innovation.

Where do they come from? Well, I used the word “describe” above, and company values are descriptive to some degree. That is, if a company does not have a list of documented values, the first place to look for them is in the culture that the company has evolved.

How do our people behave and interact with each other? How do they view customers and view their work? We might find that there’s a “work hard, play hard” or a “work-life balance comes first” mentality. We might find that there’s a very flat hierarchy or that the team prides itself on positive customer feedback. These kinds of things can differ from company to company, making them different kinds of places to work.

The way things are is not necessarily the way things should be, though. Alongside descriptive approaches to finding values, there are also aspirational and prescriptive values to consider.

For example, we may take a good look at our team and realise that there’s not a lot of diversity in it. Setting aside the creative advantages of diversity I’ve covered earlier, the members of the team or leadership team may hold values for diversity and inclusivity which conflict with the facts of current team homogeneity. Seeing a gap between where they are and where they want to be, they might include diversity as a company value to express and remind about their aspiration.

(Note that there’s still an element of description there – describing the values held by founders or leadership or the team in general, even though they aren’t yet being lived out enough to describe in reality.)

Prescriptive values are more about what kind of culture suits the business strategy. For example, a business pursuing a cost-leadership strategy might want to include values like “attention to detail” or “everyone owns efficiency”. A business depending on constant innovation might want to codify in its values that “ideas can come from anywhere”, or that “every team member is also a product tester”.

The thing to remember about aspirational and prescriptive values is that you’re starting where you are. If you have organically evolved a culture of frequent extravagant office parties and you’re wanting a culture of relentless cost-cutting, it will take more than slapping a poster on a wall. How much more so if you have problems of ingrained bigotry, sexism or elitism that you want to shift away from.

Now, while prescriptive values are chosen because they will particularly support your particular business strategy, descriptive and aspirational values are far more likely to be held in common with other companies. Diversity is a common one, these days, and no one would say, “Well, our competitors down the road are valuing diversity and inclusivity, so let’s compete by doubling down on homogeneity and bigotry.”

Of course, just because the word “diversity” or some other value doesn’t show up on a list of company values, doesn’t necessarily mean the company doesn’t value those things. At some point, there’s a line between corporate best practice that every firm should adopt (perhaps by law) and something that’s celebrated or important enough in a company to be included on a list of company values. It would be weird (but hilarious?) for a company to say something like “our team prides itself on resolving conflict without murder”.

Whoa, no murdering. That’s not how we do things around here, newbie.

Let’s listen to Stewart Lee.

As hilarious as he (always) is, I actually think it’s perfectly fine for the Car Phone Warehouse to have company values. Because it’s not just a brand, it’s also a company where people work – and those people, in addition to selling car phones, probably aren’t huge fans of racism and don’t want to be associated with it. (Setting aside the PR crisis-management angle which obviously prompted the press statement and Lee’s ridicule.)

So much for company values. What, then, are brand values? Well, while the company values are how the company and its team behave, brand values are how the brand behaves. That is, how the brand acts and speaks publicly in the course of interacting with the market. As we’ll see, that makes for some natural overlap with company values.

Because brand is a marketing tool, these values will need to be prescriptive. That is, they will be chosen depending on facts about the customers, the competition, and the business – its operations, its strategy and its history. How do we do that?

Typically, you want a mix of three sources for your brand values:

What’s most important to customers in this category?

What’s most aligned with your marketing strategy?

What’s authentic and ideally unique from your heritage?

What’s important to customers? This comes from research. I mentioned in the previous post that customers are terrible judges of their own motivations. Rather than asking them what’s important, do research on which traits positively correlate with their purchases.

I also mentioned that people tend to rate brands more highly on all metrics if they’re more familiar with those brands. That’s not a problem for us here. In fact, it works in our favour. Why? Because people tend to rate familiar brands more highly on what they expect a good brand to do in that category. And guess what we’re interested in at this point? Exactly that. So if the big brands in a competitive set get rated more highly for safety than for eco-friendliness, that tells you something about what customers expect from the category.

Note that, by definition, this is unlikely to turn up brand values that are differentiated from competitors. That’s fine – consider these brand values the table-stakes ones. They’re the price of admission in the category. They’re points of parity, but they’re important points of parity.

Next, what’s most aligned with your marketing strategy? If your strategy is to differentiate, then this is where your particular kind of differentiation comes into your brand. If your strategy is Everyday Low Prices, here’s where it shows up. If you’re in a highly commoditised category and are doubling down on distinctiveness, here’s where you capture your particular flavour of crazy.

Finally, what’s authentic (and ideally unique) from your heritage? If you’re an old brand, look at your history and ask what (if anything) makes that brand recognisably that brand through its behaviour in history. Whether you’re an old or new brand, you can look at the attitudes and intentions of founders for hints at what these could be.

For older brands in particular, these attributes can be very powerful competitive assets for a business. “60 years of poking fun” or “70 years of celebrating special moments” and so on simply cannot be copied. You can’t copy history. There is no marketing budget in the world that can reproduce Nivea’s generational memories of parents putting products on children (cream in Europe, sunscreen in AuNZ). There is no clever campaign idea in the world that can reproduce Qantas’s record for zero lives lost in plane crashes.

So, perhaps brand values are actually a mix of prescriptive and descriptive attributes, but even the descriptive ones (authentic heritage) are also useful just by virtue of being different, difficult to copy, or at the very least easy to live up to.

A certain amount of overlap between company values and brand values is almost inevitable. After all, we find our company values in part by…

Looking at how we have evolved to behave, which may overlap with authentic heritage.

Aligning prescriptions with business strategy, which may overlap with brand values suggested by the marketing strategy, which is informed by the business strategy.

For example, a business strategically differentiating on customer service is likely to have both a company value and a brand value referencing customer service. Such an element is both important to the internal culture and to the external positioning.

But still, the two are distinct even if elements are likely to overlap. One is internal, for the team, and the other is external, for the market. This echoes the distinction between company purpose and brand purpose (if we are adopting a prescriptive definition of brand purpose). The company purpose inspires and unifies the team. The brand purpose helps present a consistent and cohesive brand idea to the market.

And this, by the way, is one aspect in which I have nothing bad to say about Simon Sinek. I think he’s mostly wrong when talking about purpose and marketing. But I think he’s mostly right about the instrumentality of a company purpose for inspiring and unifying the internal team. As Jim Collins said, the engineer at Boeing is not inspired by adding 34c to earnings per share, but rather the efficiency with which her designs kill children smooth and safe flying experience her designs are enabling for happy vacationing families and weary business travellers.

But if you don’t understand that company values and brand values are distinct (even if they overlap), you end up with confusion.

Your team values diversity and inclusivity, so they appear in your company values. Then you faithfully copy those company values into your brand-strategy framework. Suddenly you’re trying to work out how to make our foot-fungus treatment brand famously diverse and inclusive.

Or… Your team values constant innovation in its quest for fun board-game activities for the whole family, so it appears in your company values. Then you faithfully copy those company values into your brand-strategy framework. Suddenly you’re trying to present the brand as innovative when parents don’t actually care about board games “being innovative” – they want quality time with the family and gentle learning curves.

Company history and business strategy alignment explain the parallels between company values and brand values, but don’t confuse them. Your company values are how you want to behave primarily as a team and a culture, while your brand values are how you want to present yourself as to customers. Despite inevitable overlap, what’s right for one may not be right for the other, and vice versa.