The Purpose of Purpose: Best vs Good Enough

We're more interested in avoiding guilt than attaining sainthood.

Anecdotally, one thing I hear a lot in relation to brand purpose and purpose marketing is that today’s customers are different from yesterday’s. I hear and read statements like this:

“Today’s consumers expect brands to be good corporate citizens.”

“Today’s consumers are more driven by their values in choosing brands.”

“93% of Gen Z/Millennials agree or strongly agree that environmental and social issues are important in their brand choices.”

Marketers combine these beliefs with a few others, like…

Customers buy the brands they like the most.

What a relief it would be if my job were fighting racism instead of promoting toothpaste.

And they come to the welcome conclusion that their job as marketers in this brave new world is to do Good things, and therefore convince consumers that their brand is the Goodest, and therefore the most aligned with consumers’ values, and therefore the most likeable, and therefore the most popular.

I made up the specific 93% number above, but I see similarly high statistics bandied about. Obviously, what survey questions specifically test is how populations answer survey questions – beyond that, we’re inferring. Here is the line of reasoning common to marketers today:

Some high percentage of our target market says that environmental and social issues are important in their brand choices.

Therefore, environmental and social issues are important in their brand choices.

Therefore, if we are the most environmentally/socially good brand to choose from, they will choose us.

I think there are two potentially unwarranted logical leaps in that thinking.

The first I’ve already hinted at. What people say is important to their purchase choices isn’t necessarily what is actually determining their purchase choices. For one, people likely want to believe that they’re more moral than they really are. And not only that, people are not the best judges of their own behaviour in general.

Rather than asking people how they make brand choices, it’s often better to ask what they think or feel about various brands, and then ask which brands they buy, and analyse the results to look for positive correlations between perceived traits and purchase. (Even then, there are confounding factors, such as our natural tendency to rate more famous brands higher on all metrics.)

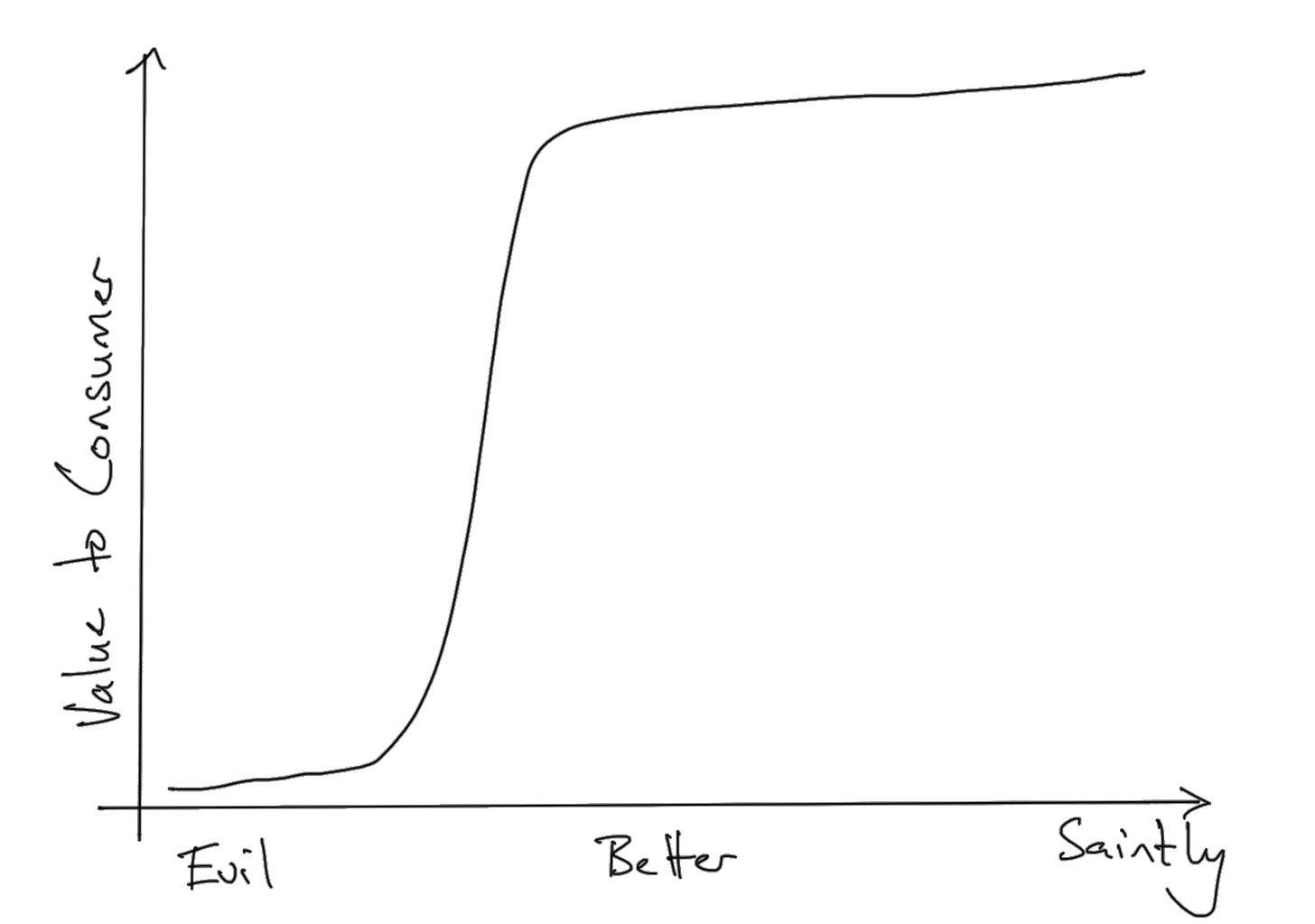

But even if it’s true that environmental and social issues are important to consumers’ choices, it doesn’t necessarily follow that they choose the most environmentally or socially “good” brand.

Ethical considerations in brand purchase are often less about trying to feel good and more about avoiding feeling bad. For example, someone concerned with the suffering of egg-laying hens would feel guilty about buying battery-farmed eggs. They don’t want to contribute to that suffering. Fair enough. But for almost all of the people who care about this, it’s enough for them to short-list their egg choices down to free-range options.

From that point on, they’re not trying to determine which egg brand gives its hens the very best treatment, nice hen scalp massages and suchlike. From that point on, they’re using other factors to decide between options – price, perceived credibility, perceived quality, etc. (And excepting price, a lot of those perceptions will be driven simply by how familiar the brand is.)

This is the difference between maximising and satisficing decision criteria. For maximising criteria, imagine a gamer wanting the best-specced graphics card for her (YES THAT’S RIGHT HER) gaming machine. Or imagine a parent wanting the safest possible car for their teenage child. These are situations where the criterion in question is compared across options and the best chosen (with some consideration to price).

“Satisficing” is obviously a portmanteau of “satisfying” and “sufficing”. It means ensuring that a criterion meets some minimum required level to be satisfactory. A huge number of our decisions are based on satisficing, largely because it requires far less energy than maximisation. If we are looking for something that is good enough, we can choose the first option that meets our minimum standards without spending any more time and effort on investigating other options.

Life would be unwieldy and impossible if we tried to make every decision through maximisation rather than satisficing. For brand marketing, it’s a hugely important concept, because a large part of the value delivered by brands is in reducing the effort required to make a purchase decision.

I’ve mentioned a few times above the inherent value of familiarity in brand decisions. Simply by having heard about a brand a lot, over a long period of time, we can infer all kinds of satisficing judgements about a product. Some of it is social proof – how bad can Nurofen be if so many people choose it? Some of it is quickfire logic – if Durex condoms were unreliable, they would have gone out of business years ago. The more low-involvement the decision, the larger the effect.

So coming back to the logic of trying to appeal to value-conscious consumers, sure, ethical considerations may be hugely important to them – for example, in that they would simply never buy a skincare product which is tested on animals. But while perceived bad behaviour may be disqualifying, that doesn’t mean that perceived best behaviour is compelling.

Add in the fact that, in some categories, all the brands are apparently trying to out-good each other. Skincare, nutraceuticals and complementary health come to mind, but there’s also electricity companies in NZ, a lot of food brands, and so on. This makes standing out very difficult.

Am I saying that it never works to be the “good brand”? No, I think it definitely does work sometimes, but in keeping with my point in an earlier article, I think that the reason it works when it works is incidental – and it’s in competitive environments or making choices which make standing out easier.

For example, in a category where no brands are particularly trying to prove their goodness credentials, a single brand can stand out and become famous as The Good One. But I think it’s the standing out and the being famous that does most of the heavy lifting when it comes to commercial impact. Ben & Jerry’s is an example of a brand that is kind of generally and famously Good (though that brand makes a lot of other very right moves that have nothing to do with Being Good).

I think there are also brands which have succeeded in associating with a particular kind of good, rather than Goodness in general. In most of the best examples, though, it’s difficult to distinguish the cause from the more general consistent brand image. For example, McDonalds has obviously narrowed its charitable focus down to sick kids, but this also supports and reinforces its general brand attributes of being for families, a fun place for kids, etc. Dove has done a very good job focusing particularly on issues of self-esteem and self-image.

Again, these are situations where a brand has consistently stood out and become famous for recognisable causes which can’t be confused with those of competitors. I find it more likely that the commercial impact of those choices is due to the consistency, the standing out, the becoming famous, and not being confused with competitors, rather than the goodness or likability of the cause.

So these are questions worth asking when you’re thinking about your brand doing good, aligning with consumer values, being likeable.

Are we trying to be best (goodest) or to reassure that we’re good enough? Why?

Are we trying to be Good in general or associate with a particular good?

What is the competition doing? Does any of this help us stand out? Does it help consumers remember and recognise us?

So much of the challenge in branding is making it easy for customers to notice and remember you for the right reasons. Yet so much effort in branding is spent instead on trying to be likeable when this more important job is not done. Purpose marketing and having a public-facing brand purpose can help make it easier for customers to notice and remember you, ideally for the right reasons.

But if they don’t, particularly if you haven’t done the work of establishing the brand and the right associations, then no matter how likeable you might be, I wouldn’t expect commercial results.