Strategy but for Agencies: Niche Strategies

So we’ve talked about the Five Forces framework for thinking about obstacles to profitability in the marketing agency industry. And we’ve talked about the difference between operational excellence and strategy. And we’ve talked about some key dimensions along which agencies differ. Let’s go back to Michael Porter and his four generic business strategies.

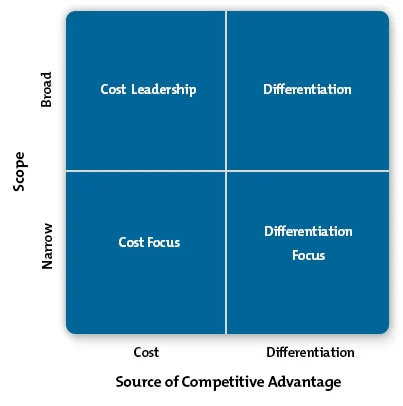

Porter’s framework for business strategies maps those strategies as varying along two key dimensions – differentiation versus cost leadership (source of advantage) and broad versus narrow targeting (scope). There are four possible combinations of these two dimensions, so we get his four strategies:

Broad differentiation

Niche (or focus) differentiation

Broad cost leadership

Niche (or focus) cost leadership

Differentiation is doing things differently from competitors in a way that adds value for customers relative to competitors. If successful, customers will either pay more for that added value (a price premium) or will be more likely to choose the offering over competitors’ for the same price (growing volume). Because adding that value usually comes at a cost to the business, charging a premium is more common, unless economies of scale1 are in play.

Cost leadership is doing things differently from competitors in a way that consistently reduces costs relative to competitors. If successful, the business can either charge less for the same value being offered by competitors (attracting more sales) or enjoy better margins by charging similarly to competitors. Because economies of scale are often involved in cost leadership, charging less for the same value is more common – as the per-unit profitability improves as the volume of sales increases.

Broad targeting means intending to offer value to most or all of the members of a market, meeting the most common needs and desires of that market. Niche targeting means identifying a segment of that market whose needs/desires are different enough from the majority that broad offerings either under-serve, over-serve or over-spend to serve them.

Successful execution of any of these strategies requires trade-offs – that is, decisions which enable one approach while reducing or eliminating the ability to perform others. Because of this, Porter judged many businesses as failing strategically by flailing about in the middle.

That said, these days a fifth generic strategy is typically recognised, and that is the best-cost strategy. This is an approach where some cost is incurred by offering higher value (differentiation) and some cost efficiencies are implemented, enabling the business to competitively serve customers who want value for money. That is, the offering may not be the best or the cheapest, but by being relatively good value and a relatively low price, customers find it more compelling than alternatives.

While it’s a valid strategy, I’m instinctively wary of it because it is precisely what many businesses claim they’re trying to do when they’re actually stuck in the middle.

So, what do these strategies look like as options for agencies?

Firstly, let’s talk about niche targeting. We’ve already talked about one kind of narrowing of focus – specialising versus integrating in services offered. I’ve touched on the trade-offs involved, including a smaller versus larger pool of industry spend to tap into. Much of what follows also applies to that kind of specialisation, except to say that in any given market, there are often a number of specialist agencies in particular services (e.g., social agencies, digital agencies, brand design agencies, strategy consultancies).

How might we define a relevantly different subset of clients? If we look at prospective clients, one big way they differ one from another is in their own industries. In some ways, these differences are relevant and significant, and in others they’re not.

Let’s consider automobiles, banks and alcoholic drinks. For each of these categories, there are very different purchase behaviours, regulatory considerations, roles of brand, relevant technical knowledge, etc. The question for a niche targeting strategy would be – could an agency specialise in one of these kinds of clients?

Yes and no. For most agencies, clients expect exclusivity within their own industry – that is, no conflicts with direct competitors. This is understandable, firstly as clients inevitably share sensitive information with their agencies, and secondly as clients could suspect their agencies of divided loyalties – commercial success for one competitor often comes at the expense of commercial success of the others.

But there is a middle ground here, where some industries benefit from category-specific expertise while there is not a lot of direct competition within it. In health and pharmaceuticals, there is a vast range of product types which don’t directly compete with each other, but all share a complex regulatory environment and best-practice marketing principles which benefit from specialisation. In Australia, agency Orchard has carved out specialisation in this sector. Sydney-based PR/earned agency 6AM has similarly specialised in nutraceuticals and complementary medicine, developing expertise in regulations and relationships for engaging key players in that value system – nutritionists, pharmacists and wellbeing influencers.

There are other options for specialisation too. An agency could specialise in particular market segments of end consumers – for example, in marketing to Gen Z or to retirees; to sports and fitness enthusiasts; to the extremely wealthy. For these to be valid strategic choices, certain things need to be true:

The narrowed focus is relevantly different from broad targeting in ways that mean it can be served more effectively (differentiation) or more efficiently (cost leadership).

Decisions can be made in the agency business which trade off advantages in broad targeting in order to improve advantages in niche targeting.

Note that this is different from simply having experience in a particular category or audience segment. The kinds of choices which make this a strategy are ones that can’t be copied by broad competitors. Usually that’s because they make the agency worse at doing other kinds of work. Again, a competitor could copy your choices, but wouldn’t – which is just as good.

A large enough broadly targeted agency hiring an expert in retiree buying behaviour is just supplementing its broad capabilities. A broadly targeted agency which has case studies of previous work successfully marketing to retirees is utilising its broad capabilities. Neither makes it significantly less capable or credible in marketing to other audiences.

For the niche strategy to work, the specialised agency needs to be able to deliver either more value than broadly targeted competitors or the same value at a significantly lower cost. If the kind of niche doesn’t lend itself to that kind of advantage over a non-specialist, it’s not a viable strategy.

But that is how a successful niche strategy translates into outsized profits (relative to the industry average). The niche agency benefits in multiple ways:

If specialisation reduces cost to serve relative to generalists, the niche agency can improve the hit rate of competitive pitching through undercutting generalists on price (reducing business-development costs).

If specialisation increases the value delivered relative to generalists, the niche agency can improve the hit rate of competitive pitching through promising more than generalists for the same price (reducing business-development costs).

If the specialisation results in a greater market share and higher volume of work, the niche agency benefits from experience (doing familiar kinds of work better and faster) and from credibility (more relevant case studies to reassure prospective clients).

If specialisation increases the value delivered relative to generalists, the niche agency can charge more relative to generalists (improving margins).

If specialisation means that a higher proportion of client work can be done by a larger number of people in the team, the niche agency enjoys efficiencies in managing capacity (less profit lost to freelancers or turning down work).

If the agency becomes well known for its specialisation, prospective clients may seek them out without any competitive pitching (further reducing business-development costs).

Well, that all sounds pretty great. What are the downsides of specialisation? Why don’t more agencies do it? In addition to some of the obstacles listed in the last article…

Some specialisations might incur some risk. For example, tourism is a valid contender for specialisation – lots of clients who aren’t in direct competition (and in fact benefit from cooperation), relevantly different marketing needs and specific audiences. But if, say, a global pandemic were to arise, that specialist agency would take a much bigger hit than a generalist.

If there aren’t significant barriers around the strategic position, the attractiveness of the specialisation will attract multiple agencies. That’s not the end of the world, as it basically creates a strategic group of agencies outcompeting broad agencies. But it adds a new strategic challenge – how now do you compete with other agencies doing the same thing as you? The group as a whole may still enjoy competitive advantages, but within the group you’re a commodity being squeezed on price by intra-group competition. Social agencies quickly discovered this phenomenon in the early 2010s.

Perhaps most significantly, some specialisations may reduce the prospective market to a point where attaining the size necessary for economies of scale is impossible. I know I’ve said that there aren’t so many economies of scale in agencyland, but there are still some and they have an exaggerated effect at the smaller end of things. An agency of ten people is still likely paying a lot in fixed costs for its management, and wouldn’t pay much more for that management if the agency tripled in size.

On a psychological level, a niche strategy can be difficult to follow through on. When business is quiet, it’s tempting to start accepting or pitching on work that isn’t quite in line with the strategy. The margins might not be there, but cashflow is king and bills need paying and mouths need feeding.

So, what kind of choices can a niche agency make to improve profitability?

Doing the same kind of work over and over may allow the agency to develop templating. Strategy frameworks, audience profiles, project plans, all kinds of things require a lot of effort to create the first time, but can then be repurposed with some tweaking over and over. That cuts down the cost to serve. Why can’t broad agencies do it? Well, they can, but because their relative volume of that kind of work is much smaller, there are fewer opportunities to benefit from it.

A particular focus may allow the agency to pay for expensive specialists who improve the value to clients and increase the credibility of the agency to prospective clients. Why can’t broad agencies do it? The volume of that kind of work isn’t there to fully utilise/justify such an expense.

The niche agency could produce thought leadership like white papers, research projects and training seminars. This grows the agency’s credibility with prospective clients. Why can’t broad agencies do it? They don’t gain much from the expense, and the appearance of specialised expertise could detract from their perceived value in other areas.

Similar to templating, niche agencies may develop specialised processes or ways of working which are particular to their focus. These can lower costs and/or improve the value of the output of the work. Why can’t broad agencies do it? Well, they won’t when those processes come at the expense of other kinds of work. And with the lower relative volume of that kind of work, they might not have an opportunity to develop them in the first place.

The niche agency may also develop relationships with a network of related agents. Journalists, academics, researchers, industry bodies, influencers, venues, key opinion leaders, non-profits and businesses can all be part of an ecosystem which creates value related to your niche. This can help you add unique value to your offering. Why can’t broad agencies do it? It’s not worth their time and they don’t have the volume of interactions to build up strong relationships.

These are the kinds of choices an agency must make to benefit from niche targeting. What’s key here is that you can’t simply declare yourself a niche specialist and then merely apply overall industry best practices to that kind of work. If you do that, you’re just a generalist who has randomly limited your pool of prospective work. You have no cost or value advantage over broadly-targeted agencies who are competing with you for the same kind of work.

Your goal is for those broad generalist agencies to hear that you’re competing on a pitch and they bow out because they know they can’t match your offering, your price, or both. If nothing about your business activities gives you either of those advantages, they will have the advantage. Why? Because they’re probably bigger than you, able to throw more resources at the pitch, claim value-adds that come from a broad strategy (next article) and are enjoying some of the economies that come with that size (e.g., their $400k of management costs are spread over 50 people’s worth of work instead of 10).

I’ll say it one more time for those in the back. Niche strategies do not work like this:

No business strategies work like this, however much we might want them to. You can’t simply declare yourself a specialist. You need to make hard decisions which involve trade-offs to either add value or reduce costs in ways that broadly targeted agencies cannot or will not do, which will likely make you less competitive for work outside of your niche targeting.

If you’re not familiar with economies of scale, the short story is that it’s similar to bulk-buying discounts, but for production in a business. That is, it’s more expensive to build a lot of something than to build just one, but the cost per item comes down the more you build. More specifically, it’s about spreading the costs that remain the same regardless of how much or little work you’re doing (fixed costs) across more revenue-generating work. Basically – the more sales you make, the more profitable each sale is.