Strategy but for Agencies: Agency Brands and Diseconomies of Scale

Okay, I am back to fighting-fit form, or at least not bed-ridden and feeling sorry for myself.

I want to cover two completely unrelated things today. Firstly, the effect of brand on agency strategy; and secondly, potential diseconomies of scale that agencies might face.

Let’s remind ourselves of what brand equity actually is. Brand equity is the differential effect of brand knowledge on customer responses to the marketing of the branded products or services. In other words, what is the difference between a completely unbranded product or service and the exact same product or service with the brand attached? How much more will they pay and/or how much more likely are they to buy it?

This boils down to metrics like sales per dollars spent on marketing – or, put another way, dollars spent per sale. But while that’s the end result, the effects of brand equity are mediated through a complex collection of contributing impacts:

Brand recall – how easily does the brand come to mind when category needs arise?

Brand recognition – how many people know the brand when they see it?

Category associations – how many relevant category needs is the brand associated with?

Brand perceptions – what positive associations does the brand have with attributes important to decisions in the category?

Brand distinctiveness – how difficult is the brand to be confused with competitor brands?

Trust – especially important for categories in which the product or service quality is obtuse; that is, you won’t really know how good it is until you’ve already bought it.

In some ways, brand is the last refuge of scoundrels in business. Every brand benefits from brand building, but in commoditised categories with no real differentiation in value from one product to the next, brand is the only real counterbalance to price. Unless you can increase margins from the other end – lowering costs per unit more than competitors – you get profit squeezed out of you along with everyone else.

If it’s a rule of thumb that brand becomes relatively (even) more important in commoditised categories and I’ve been saying that Agencyland is largely commoditised, then it stands to reason that brand should be a priority for agencies unable to differentiate in any other way.

Brand is an intangible asset owned by a company, so we can analyse it with the VRIO framework to determine whether or not it can become a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Does it create value for customers? Yes, in the form of confidence and reassurance of quality in advance of the actual work being done. Is it rare? Brand in general is not rare, but the more well known and associated with category quality attributes it is, the rarer it becomes. Is it difficult to imitate? Yes, because it takes years of investment to build up a brand. And are agencies organised around taking advantage of the asset? Yes, they typically are, one would hope.

So a brand that has been built up over time can be a source of advantage. But if we assume that building up an agency brand is best practice and there’s nothing stopping any agency from doing the same thing, then we can assume that all agencies will work to build their brand assets over time. So agency brand just becomes a proxy for agency age – and older agencies have the advantage.

Is there no scope for conscious choice here? There is, I think. Firstly, agencies can be better or worse at promoting their own brand. I won’t name the agency, but a few years back I heard one agency described as “not doing any better work than anyone else, but PR’ing their work better than anyone else”. Well, more power to them. In retrospect, those efforts have paid off. So you can’t just let agency brand happen – agencies need to market themselves.

Secondly, typically in a commoditised category where every player is resorting to competing purely on brand, brand distinctiveness becomes even more important than it usually is. All agencies are building brand over time to some extent, and the effect of that fame and familiarity is first of all: “Oh yes, of course I’ve heard of them.” That brings with it certain reassurances of quality and reliability – after all, a poor-quality and unreliable agency wouldn’t have lasted long enough for you to have heard of them.

But as multiple agencies have this level of fame and recognition, those brand effects become table stakes rather than a competitive advantage. The well-known agency becomes one of a number of well-known agencies and they don’t particularly stand out from one another. Collectively they have an advantage over unknown agencies, but within their own group they’re competing very similarly.

This is where standing out for the sake of standing out has some advantages. The goal is for prospective clients to not just think “oh yes, I’ve heard of them” but to further think “they’re the ones who ___________”. What words fill in that blank matters less than that words fill in that blank.

I mean, obviously you don’t want to be famous for something bad – “oh yes, I’ve heard of them, they’re the ones who treat their clients like shit”. But as long as it’s positive and unique, almost any positive thing will do. Keep in mind, we’re assuming that this agency doesn’t actually do things significantly differently from any other agency – they’re all just competing with best practice. If you were doing something differently in a way that creates value for clients, then obviously that’s what you want to be famous for. But in lieu of that, pick a positive attribute that isn’t owned by anyone else and consistently claim it for yourself.

What kind of positive attributes? You can choose from either category traits or non-category traits. Firstly, here are some example category traits:

Reliability

Innovation

Latest technology

Ease of doing business

Cultural awareness

Humour

Now, every agency is trying to be reliable, innovative, using the latest technology, easy to do business with, culturally aware and able to be humorous. And if an agency were to try to own the highest levels of association with one of those traits, they wouldn’t say they’re dropping the ball on the others. But becoming famously associated with just one of them gives the agency an excuse to stand out from the others, for something generally positive.

Maybe the trait itself will be compelling for some clients. But more likely the positive effect of the brand is to just stand for something recognisable, to make the brand more distinctive than the Generically Good competition. Similarly, maybe some people buy Volvos because they’re particularly concerned with safety, but probably the main effect of Volvo’s brand association with safety is to be recognisably something in the auto category.

What about non-category traits? My favourite example of a brand deriving distinctiveness from non-category elements is Compare the Market.

Insurance comparison websites are a very commoditised category. The competitors may vary slightly in quality of user experience, but mostly they were just competing on price and very competitive (expensive) search marketing. Compare the Market launched their brand platform “Compare the Meerkat”, with its bizarre Russian-accented meerkat spokesperson and came to completely dominate the fragmented category.

There are all kinds of rationales for why this worked – not least of which is the humorous way of driving the business’s URL into audience’s brains. (Consider the massive value of people just remembering “comparethemarket.co.uk” and going directly to the site without clicking on search ads for hugely expensive search terms like “car insurance”.) But I believe one of the biggest ones was simply standing out for the sake of standing out.

Ironically, if Compare the Market had tried to stand out by owning a category trait like “best prices” or “most trusted” or “widest range of insurers”, they wouldn’t have stood out as much.

Can agencies learn something from this? There’s probably something there. There is some danger in zaniness for zaniness’ sake because, for some buyers, zaniness may negatively correlate with reliability. But at the same time, what are clients looking for in agencies? They’re looking for creativity they can’t generate internally. An agency which stands out in some surprising way could enjoy some advantages.

Does the agency have a key figure who could become well known for being controversial? Or stand out in some other surprising way?

Could the agency host bizarre/surprising industry events?

Could the agency publish some kind of surprising annual industry publication?

In the absence of any real differentiation, fame for its own sake, behaving in ways unexpected of an agency, could potentially yield benefits.

The other sort of half-post I wanted to talk about today was raised with me by an agency owner when talking about size. In contrast to many of my points about economies-of-scale challenges at the smaller end of the agency-size spectrum, he suggested that there could be diseconomies of scale as an agency’s projects get bigger.

Here was his reasoning:

For smaller agencies with fewer resources, they’re forced to be lean in delivering on projects – there’s no other choice.

As clients and their projects get bigger, that leanness disappears and is replaced by a kind of institutional redundancy in resources – more people in each meeting, more internal reviews on work, more people assigned to produce the same deliverables.

And so the relative cost to serve increases with the size of the project – and margins decrease.

There are a few interesting things going on here. The first thing that occurs to me is that it’s not the size of the agency or the size of the clients that’s necessarily associated with the diseconomies, but the size of the projects. It is true that larger agencies tend to have larger clients who tend to have larger projects, so there’s some correlation there. But it’s the project size specifically which is supposedly creating diseconomies of scale.

Setting that aside for a moment, the other interesting thing is that could you could potentially have both economies and diseconomies of scale operating at the same time.

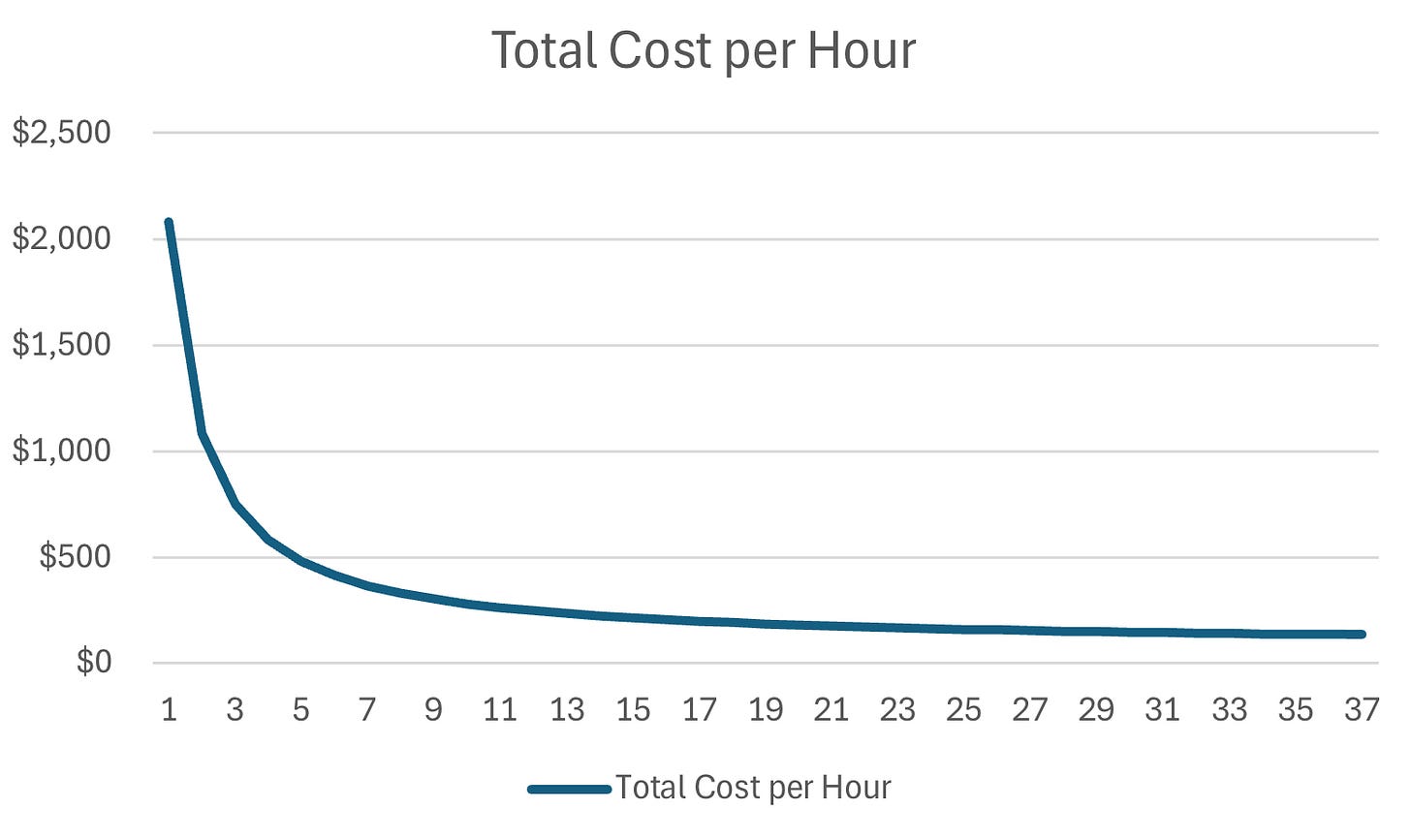

Here’s what economies of scale look like, in this case with fixed costs of $100,000 being spread over more and more hours with an $80/hour variable cost:

(The x-axis is counting 100s of hours.)

As I’ve said, at the smaller end of the spectrum, the economies of scale have a huge impact – typically the cost of management, office lease, etc. But at the larger end of the spectrum, the marginal benefits of scale get lower. We could get a bit more accurate and recognise that fixed costs themselves can increase in steps with size – for example, the cost of a second office in a new city or an additional layer of management to handle a significantly larger team. But for now, let’s keep it simple.

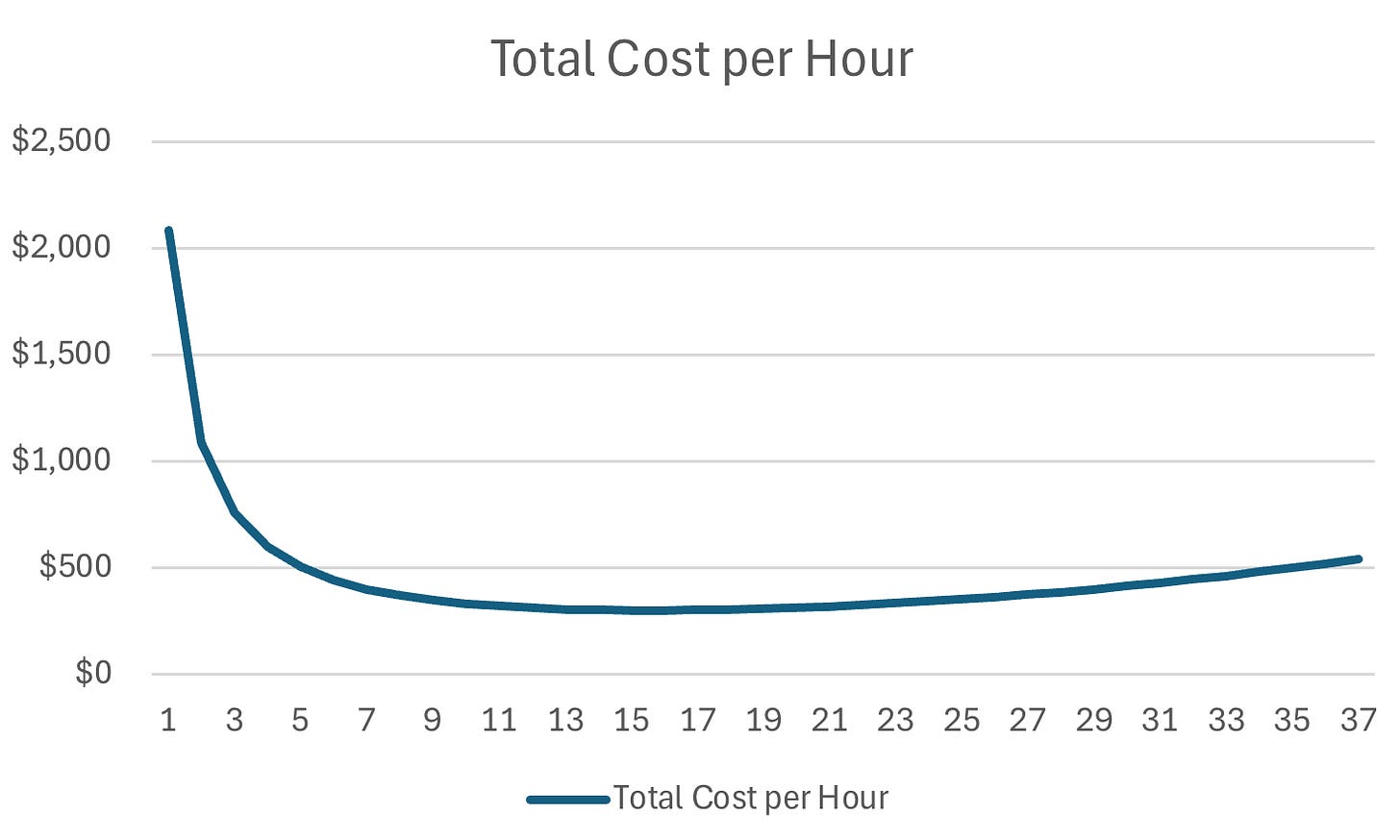

And here is what the aforementioned diseconomies of scale might look like:

And now here is what they look like combined:

With the vying tensions of economies of scale having a larger impact at the smaller end and diseconomies having a larger impact at the larger end, we end up with this implication that there’s an ideal agency size for profitability. A sweet spot which, in this arbitrary hypothetical, sits around the 1300-head-hours mark.1

It’s an interesting thought. However, the model above assumes ever-increasing diseconomies of scale, when it’s more likely that agencies reach a certain cap of bureaucratic inefficiencies and stay there no matter how big the agency, the client or the project gets. And it also assumes that these diseconomies are inevitable, which is probably debatable.

Firstly, was the smaller team really more efficient? It showed up on the books that way, but it’s possible that the smaller team was actually just overworked and the apparent loss of efficiency as the budgets increased reflects a correction back to the norm. That is, the same amount of work being done by five people who go home in the evenings versus three people who barely see their families.

And even if the unnecessary bloat is real, is it actually unavoidable? Usually when we talk about diseconomies of scale, we’re talking about unavoidable features of the nature of an industry. If the bloat is unnecessary, best-practice project-management and team-management techniques should be able to keep it in check – and as an agency grows, methods which worked in the past may no longer be fit for purpose.

But finally, if the inefficiencies really are unavoidable and are associated with project size (as opposed to client size or agency size), there could be a real benefit to agencies finding ways to keep projects to an optimal size. If that means not going after the really big clients with the really big projects, it could look like an agency that grows primarily through acquiring more mid-sized clients rather than the typical path of larger and larger clients.

Anyway, those are two thoughts that probably couldn’t fill a whole post in themselves, so I threw them together. I think they raise some interesting questions:

How can an agency build a genuinely valuable brand – that is, one which enables it to win work more easily, attract talent more affordably, etc., despite there being no functional difference in value offered?

Is there an optimal agency size, client size, or project size for profitability? What causes one client or project to cost more to serve than another? How must an agency’s project- and team-management processes evolve with growth to prevent increasing cost to serve?

For God’s sake, I invented ALL of these numbers to illustrate this point, do NOT go screwing with your business to match this entirely hypothetical sweet spot.