The Chances of a Good Idea

Why creativity in business is hard and what to do about it

I want to talk a bit about creativity. While I’ll focus on agency processes to illustrate, the same insights are applicable to any business that requires new ideas – that is to say, any business at all.

When I’m running training for agency teams, I often ask them what it is that creative agencies actually do. What do they produce and sell? What do their clients pay them for? They come up with a variety of answers, but one is fairly inevitable: agencies produce ideas. Ideas are what they believe their clients couldn’t produce on their own – or not as well as a team of idea-having experts would have.

For a business or business unit, ideas are weird things to produce. With physical products like lawnmowers and services like haircuts, a business can develop processes which will reliably, consistently and predictably result in the desired output or outcome. But as anyone who’s ever tried to have a good idea on command knows, there’s seldom anything reliable, consistent or predictable about it.

The key difference here is that the delivery of lawnmowers and haircuts is mechanistic/deterministic. If you do step 1, then step 2, then step 3, and so on, eventually you’ll end up with a complete lawnmower. It takes roughly the same amount of time each build. And if it’s bad or incomplete or takes too long, the explanation will lie in something going wrong in one of the steps.

But ideation is a different beast. Can you tell someone to have a good idea and ask them how long it will take? It’s possible (though improbable) that they’ll have a good-enough idea within 10 minutes. It’s also possible (but improbable) that they won’t have had any good-enough ideas after four weeks. This is the probabilistic (or stochastic) nature of ideation. At any given time, there’s a chance of having a good idea, and that chance is somewhere between 0% (impossible) and 100% (inevitable).

Perhaps a better way of looking at this is to say, for any given idea, there’s a chance between 0% and 100% of it being a good enough idea (by whatever our standards). When someone is trying to come up with good ideas, they’re not (usually) just sitting there waiting for inspiration to strike – they’re coming up with ideas in general. And each one has a chance of being good enough.

Note: For simplicity here, I’m going to be assuming a constant rate of idea quality – that is, for example, that it’s just as likely to have a great or terrible idea on the first day of ideating as it is on the fifth day. That’s not quite how it works in real life, but I’ll address that later.

For argument’s sake, let’s say that the probability of an idea being good enough is 4%. So there is a 4% chance of the first idea being good enough. It does happen! But it’s very unlikely. How about the first ten ideas? There’s a 33.5% chance that at least one is good enough. After the first 30 ideas, there’s a 71% chance that at least one is good enough.

Things get rougher for most agency scenarios, where typically three “good enough” ideas are presented to a client for selection. After the first 30 ideas generated, there is only an 11.7% chance of at least three of them being good enough.

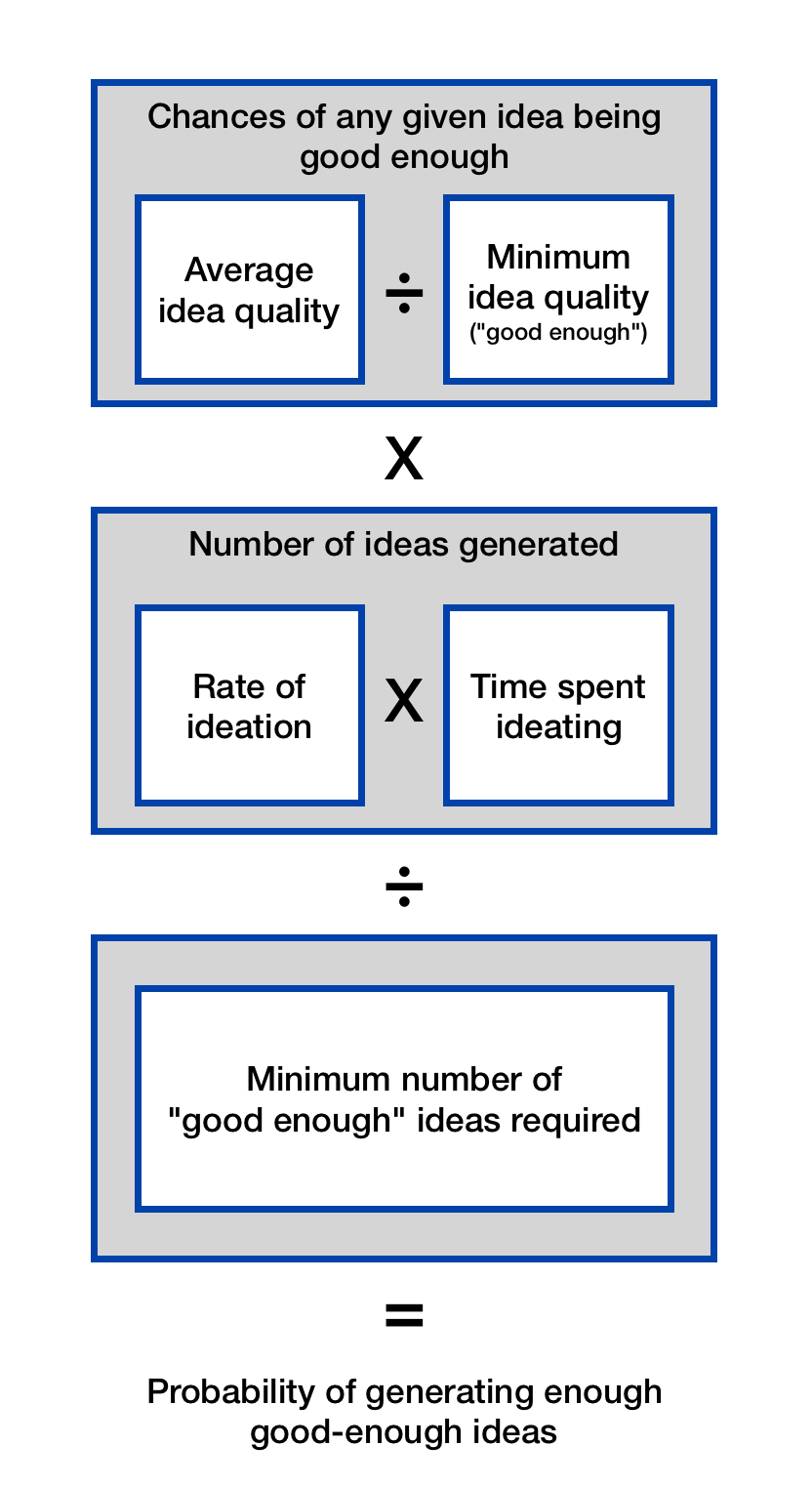

So let’s look at the different factors involved in the success of this ideation activity. On the face of it, there are three main factors – the probability of any given idea being good enough, the number of ideas being generated, and the number of good-enough ideas required. However, these can be broken down further.

The probability of any given idea being good enough is determined by both the average quality of ideas generated and the standard for “good enough”. In other words, to improve the probability of ideas being good enough, you must either have better ideas or lower your standards, or both.

The number of ideas being generated is determined by the rate of idea generation and the amount of time spent generating them. So to increase the number of ideas generated, you must either have ideas faster or spend more time having them, or both.

Imagine a situation where a creative duo are asked to come up with a great idea within three days, and the standard is quite high – there’s only a 2% chance of any given idea being good enough. Let’s say they can average 20 ideas a day. After one day, there’s a 33% chance that one of their ideas is good enough. After three days, it’s 70% – still a 30% chance that no ideas are good enough.

What can we do to improve this situation? Logically, our options are…

Improve the average quality of the ideas, for example with a better creative brief.

Lower our standards for a good-enough idea – if we double the chances of an idea being good enough to 4%, we get a 90% success rate after about three days.

Lower our standards for how many good-enough ideas we need.

Increase the rate at which ideas are being generated, for example by increasing the number of people ideating or by the adoption of ideation methods which generate ideas more quickly.

Give them more time – for a 90% success rate, they’d need to generate 114 ideas, which is just under six days of work.

Anyone who’s worked in a creative agency knows what tends to happen in the real world. After a given amount of time, the ideas generated are evaluated. If not enough are good enough, a call needs to be made – do we run with the best idea(s) available (lower standards) or burn more creative resource (increase time) and possibly throw another team at it (increase ideation rate)?

But lowering standards and burning more head hours are the least desirable options for an agency. Both risk the client relationship (disappointed by quality or timeliness), agency reputation (idea quality or agency reliability) and team morale (uninspiring work or burnout through spinning wheels creatively). Not to mention the labour cost of further ideation.

The next few posts will explore these dynamics from a few different angles. Stay tuned.

The value of an idea is largely subjective until it is tested. i.e. the ideas alone are not of tangible value unless an additional factor is introduced.

Prototyping and associated testing methodologies should also be considered when presenting 'ideas' as the world is full of success and failure stories that contradict clients preconceptions of what constitutes a 'good idea'